Some people have asked me about my thesis, so I figured we'd take a short hiatus from the Math/God conversation. Here is the conclusion of my thesis, which is entitled 'The Philosophy of Character Vertigo: An Essay on Choice, Anxiety, Freedom, and the Self.' The final chapter, Our Vertigo, details my conclusions in the thesis and references, but does not rely upon, the literature I used. Even if you are unfamiliar, you can still appreciate my attempt to answer the question, "How do characters in literature relate to us real people here-in-the-world?" Enjoy!

"Characters in literature have meaning for us in real life. Literature, as an artistic form, is humanity's best creative attempt to understand its existence. Vertigo, as I have demonstrated in my analysis of the protagonists’ choices and the authors’ intentions, is a powerful metaphor with which to describe the fundamental anxiety that we all feel in every choice we make. Character vertigo, thus, is a new literary model that expands our philosophical insights about literature, a paradigm indebted to fundamental ideas in existential philosophy. While I am hesitant to assert that my model implies a purely existentialist analysis of a literary work (as the model does not necessarily liken the character’s outlook to an existential philosophy), it is certainly a creative, useful mode for understanding essences, selves, and ultimately the deepest anxiety in the subject it deconstructs.

Essences, as mentioned in the introduction and in chapter 2, are the key themes and conflicts addressed in any Bildungsroman. This is not the same as Sartre’s notion of essence; he believes that essence is a meaningless concept that does significantly less ontological explanatory work than existence (this is what he means when he asserts in Existentialism as a Humanism that ‘existence precedes essence’). My conception of essence is more like a combination of recurring symbolism, character conflict, and moral significance. Therefore, character vertigo relies upon finding a character’s essence and extrapolating it into a more substantial interpretation of his self.

When we look at Tereza’s essence, therefore, we factor in her recurring nightmares, her failed relationship with her husband, and her personal conception of morality, with a particular interest in how these events affect her self. When we look at Horner’s essence, we are interested in his constant reference to the Laocoön bust, his arguments with Morgan, and his reflections about his physical paralysis. Looking at Antoine Roquentin’s essence, we examined his recurring nausea, his discussions with the Self-Taught-Man, and his opinions about existence. Essences, therefore, are descriptive accounts of a character’s change through the various events that happen in their narrative lives. But we need not limit essences to characters in fiction; in the previous chapter I attempted several conjectural arguments as to how we might identify essences in authorial intent. What is the essence of Kundera’s intention in writing The Unbearable Lightness of Being? It was the archetype of an artist, living in exile, yearning for a place he could no longer return to. I need not re-iterate each individual claim about our authors’ essences here; suffice to say, we may speak of essences beyond a mere literary phenomena.

Also paramount in the instantiation of the character vertigo model is an understanding about the self. As I articulated in the introduction, the self is related to essence, though they are not the same. We need the self in order to track changes in our constitution. If we had no basis, no static self with which to compare, we would not have any conception of being continuous and complex beings . The self is an abstract construct, a being-for-itself, that allows an individual to connect his current body and mind to previous iterations of the same body and mind. Therefore, if our self may be regarded as a type of ubiquitous common denominator, essences can be thought of as the process of dividing. Only in finding essences – conflicts, moral theories, and anxieties – can we locate the self, itself a type of indivisible ontological essence. That said, the self also defies definition; we cannot say that Tereza’s self is her fidelity, nor can we say that Horner’s self is a lack of morality. These are descriptions of essences. The best description of the self that I can offer is a non-semantic consciousness that exists only for facilitating individual change, which it achieves through the integration an individual’s evolving qualities and static qualities, simplified into a consistent self-referential story. Perhaps this definition needs some further unpacking.

Given the fact that the self resists definition as a concrete object, we must understand it as an abstract premise. The self, a construct in consciousness, need not be weighed down by the confines of language or objective meaning; to define the self with words or in relation to other established concepts is to unnecessarily limit its definition. Therefore, I determine the self to be non-semantic. Secondly, the self arises from an anxiety of individual consistency; the self is the answer to the paradox of how I am constantly changing whilst remaining myself. Therefore, it exists (or at least we invent it) to facilitate changes in our essences, and other archetypes we become during the course of our lives. In this sense, the self integrates new essential experiences with old ones – this, I believe, as a process which the subject is consciousness of. Additionally, the self gives order to potentially meaningless existence; the self inspires an individual to regard his life as more than a random amalgamation of causes and effects. The self forces us to acknowledge the totality of our lives into a meaningful story about change, conflict, and the freedom of choice (and hence it is self-referential). We invent the self every time we think of our lives as more than a series of deterministic biology, chemistry, or physics. One identifies the self when he understands that he is the protagonist in the story of his own life. The birth of the self, and its presence in every conscious being, helps us make the final transition in the character vertigo model. How does character vertigo relate to real life?

If instantiating the self means acknowledging life as a story, than analyzing the self is analyzing the protagonist in that story. When we analyze the protagonist in a narrative, we imagine his self in an effort to create his hypothetical consciousness. It is not the author, then, which creates consciousness for the characters, it is the reader who, every time he makes a mental projection of the character, offers a real-life consciousness to an abstract, hypothetical being. Consciousness, therefore, according to my description, does not exist exclusively in the physical world; we do not need a body to necessarily postulate consciousness . And because literature is a theoretical realm in which any logical possibility can be explored, than the story of a character’s life – insofar as he resembles us – is analogous to the story of our own.

Why does it make sense to speak of a character’s intention? How can we regard characters as autonomous? How can we put forth moral responsibility and offer moral judgments as to a character’s decisions and choices? Why do we sometimes feel more connected to literary characters than people in the real world? The answer to all these questions is that we fundamentally regard characters as we do people; they are our best analogue for understanding ourselves. We first notice that a character participates in certain essential archetypes, instances which are familiar to us and so we begin to identify with them. We then see these essences as facilitating an inner-conflict with the self. When we conceive of a character as having a self, we

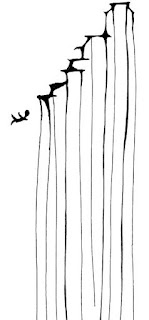

unconsciously project his consciousness through our own mind. When we become aware of this process, we regard the character as our counterpart, a similar being that we can learn from by observing. When we analyze this process, in the guise of existential claims about human anxiety and angst, we create a new story altogether, a story of character vertigo that traces the development of the individual (whether theoretical or real) from his birth to the brink of the precipice. In understanding this story about the other, we can better understand ourselves, identify our own precipices, and choose to jump (or not).

No comments:

Post a Comment