With my Math + God conversation cerebrally derailed, I digress to a topic that has been on my mind for quite some time.

Here is the question: How ought we to judge our fellow people if not by their previous actions?

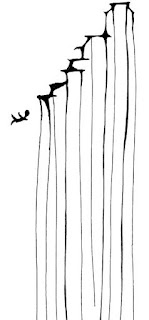

Here's the problem: If we judge people by their previous actions, are we not condemning them to repeat the sins that they have already committed?

Here's what I mean: As a person looking out for my own interests, I certainly don't want to get screwed over by others. So there's definitely a pragmatic function to judging other people, especially those who are close to me. The next logic question is simple to formulate, but difficult to answer; what parameters ought I to use in judging others, particularly those whom I have deep relationships with?

If I judge someone by what they have previously done, expecting them to repeat old mistakes, I deny them the benefit of changing old behavior.

If I don't judge someone by what they have previously done, I make myself vulnerable to incurring emotional harm as a result of them intentionally or inadvertently repeating their mistakes.

How can we know if someone has truly changed? Does Hume's for apply even here; ought we to not take for granted that one's future actions will resemble one's previous actions? Or are human beings different than ontological/cosmological challenges?

To be frank, I think the expectations are in the eyes of the beholder. I can chose to accept or reject someone's history, heinous as it might be, and that will only affect my conception of our relationship if I choose to believe that 'future deeds resembles old ones.'

Upon further reflection, it seems that the situation would have a significant stake in this debate. What I mean but this is that if one particular predicament drove me to steal, that does not necessarily mean I am a chronic thief. Even if I have stolen my whole love (say, because I have been poor and hungry), perhaps I shall not steal once I have money whereby I can legitimately purchase bread. Are you, as someone who is emotionally involved with me, ready to label me a thief for life because I have stolen before? When do I earn the benefit of the doubt?

How long must one not steal in order to escape his perceived nature as a thief? Does resisting the urge to steal, even if you have stolen on previous occasions, cease your characterization as a 'thief'?

How can religion preach forgiveness when it is so quick to call us sinners? How can spiritual rehabilitation be truly possible if we are unable to escape our transgressions against each other?

I cannot definitely answer a single one of these questions, but, in what follows, I will do my best to try, and to be ethically consistent.

1. Those who we are emotionally involved with ought not to be judged by us for sole actions in the distant past.

1.1 Actions done habitually, such as compulsive gambling, infidelity, or drinking, may not be easy to forgive, but forgiveness is essential to maintaining relationships.

2. Actions are temporal; so to should judgments be. There is always an opportunity to change actions, and so there ought always be the opportunity to change judgments.

2.1 We are entitled to act poorly and justly throughout our lives. This is part of our design. We are therefore obliged to be judged appropriately by our actions, but not absolutely.

3. It is unfair to keep the judgments of those who are emotionally close to you to yourself. Part of being in a relationship of any depth means communication, especially communicating the terms and conditions by which you stand to be judged.

4. The sinner/forgiveness paradox is an outdated model which is no longer effective. We are neither sinners nor are we saints. We are people. Judgment is the new guilt. Fairness the court. And apathy the executioner.

5. Rehabilitation from previous actions is possible but can only be done when judgments rendered against you are weakened with the potential of forgiveness.

5.1 If you are wronged by someone you love and what to make amends, YOU must foster a sense of forgiveness to them if you expect any change in their behavior. To not do so is to be unfair.

6. Moral judgments are not absolute; the above rules are guidelines that have come to me with my life experience. Every individual is entitled to form his own which have no more or less legitimacy than mine.

6.1 The key here is that we outline something that others who love us and who we love can rely upon. There is nothing more hapless and deprecating than being judged in ways which are unknown to you, by standards you've never heard, and with expectations impossible for you to meet.

My 2 cents.

Read the Rest